Regret: Everything You Need to Know and How to Avoid It

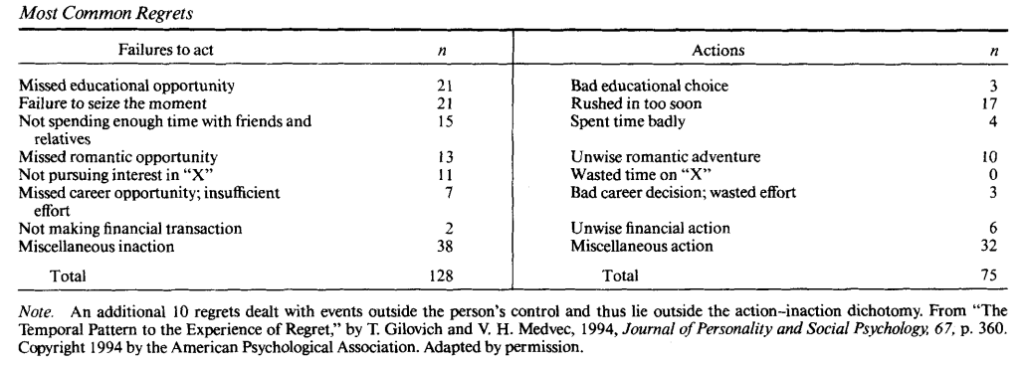

Every person is born into this world condemned to a life full of contemplating various existential issues; What is my purpose, meaning in life, and what regrets will I have in the end? I will be discussing the latter, as I show how one can avoid a life full of regret. The best way to avoid a regretful life is by, “more frequently throwing caution to the wind and acting boldly more often.” 54% of the regrets appeared to be regrets of inaction, whereas only 12% appeared to be regrets of action.

What Is Regret?

Regret has been ubiquitously confused with making mistakes or the feelings we have towards those mistakes. For the sake of this article, I will use Landman’s inclusive definition,

When Do We Regret?

The moment we regret is different depending on the regret being a result of action or inaction.

Action

Because action tends to be more salient, our regret is more immediate. That is not to say that we can’t feel regret for an action that we did in the distant path, but it is to say that the precipice of regret we feel quickly follows the action.

Inaction

For inaction, the larger the temporal distance from the point in which we didn’t act, directly correlates to the amount of regret that we will feel towards not acting. Inaction is less salient because inaction or not choosing is considered to be the default rather than the opposite end of action in the spectrum of decision-making. After enough temporal distance, we forget most of our internal reasons as to why we chose not to act.

What Do We Regret?

Why Do We Regret?

The reasoning as to why we regret is once again dependent upon the regret is a result of inaction or action.

Action

The main reason that we regret action is because of the saliency of it. The negative outcomes brought on by actions feel more troublesome than the same outcomes brought on by inaction. If I failed a test because I chose to go to a party the night before, I would regret that more than if I had stayed home and still failed. Action provides a more noticeable target for psychological repair work than failures to act. Also, because inaction is often viewed as the status quo and action as a departure from the norm, people generally feel more personally responsible for their actions than for their inactions. However, our brain deals with the consequences of regret by action far better than by inaction. Our brain has many tools to reduce our cognitive dissonance.

Dissonance Reduction

Humans have two basic motives: the desire to feel good about themselves and the desire to be accurate about the world. Dissonance reduction focuses on the motive of maintaining our self-esteem. Cognitive dissonance is the discomfort that people feel when they behave in ways that threaten their self-esteem. Regretful decisions are something that can negatively affect our self-esteem and so there are ways we reduce the discomfort.

Finding the silver lining

Noting how we have learned from a negative experience is one of the most common ways that we cope. We offset the discomfort we feel towards a regrettable outcome by finding the silver lining. “I learned so much,” is the most classic silver lining that people internalize after a negative event. The only way to learn is by making mistakes and stepping out of your comfort zone. You can not engage in dissonance reduction with a regrettable inaction because there is no way to produce a silver lining.

Postdecision Dissonance

Postdecision dissonance can be described as the dissonance aroused after making a decision, typically reduced by enhancing the attractiveness of the chosen alternative and devaluating the rejected alternatives. For example, If I chose to go to the University of Florida rather than Florida State University. I will subconsciously find reasons to love UF and dislike FSU after I make the decision. Postdecision dissonance is all about convincing yourself and justifying why the decision you made is the right one. Knowing this, one can assume that any decision they make is justified as the right decision, thus deciding is not that big of a deal. The only thing that matters is choosing.

Inaction

One of the main reasons that we regret inaction is because of the Zeigarnik effect; people tend to remember incomplete tasks and unrealized goals better than those that have been finished, accomplished, or resolved. I extrapolated a bit and presumed that the reasoning for this is that we see completion, positivity, and success as a default. This is why in the news, the most exciting stories are those that are horrific. Good is the baseline, so anything below that baseline is remembered more because it is a deviation.

Infinite Possibilities

Also, when we think of times when we didn’t act, we fantasize about all the “what ifs,” and all of the possible branches that could have come from action. Reminiscing about inaction leads us down an infinite path with infinite options and of course, we only think of the good possible outcomes. We have already experienced the consequences of our regretted actions. Regrettable inactions that happened to us in the past are just as with us in the present because the possibility that surrounds our failure to act is limitless.

The Only Option

Inaction is far more detrimental to us than action because there is no way to reduce dissonance. Also, the regret of inaction is directly correlated to the distance from the event. As our regret increases, we end up on our deathbed fantasizing about all of the “What ifs.” The only way to avoid a regretful life is to act and decide. Be more spontaneous, be more impulsive, go on a vacation, go on that date, take that class, learn that skill, and don’t wait until it’s too late to become the person you want to be. We use dissonance reduction to justify any choices that we make and so have no fear over possible outcomes.

People are less susceptible to regret than they imagine, decision makers who pay to avoid future regrets may be buying emotional insurance that they do not actually need. We anticipate more regret than we actually feel after we make a decision. Fear the consequences of inaction rather than action. View yourself through the eyes of your elderly self and act in ways that you would wish they had acted.